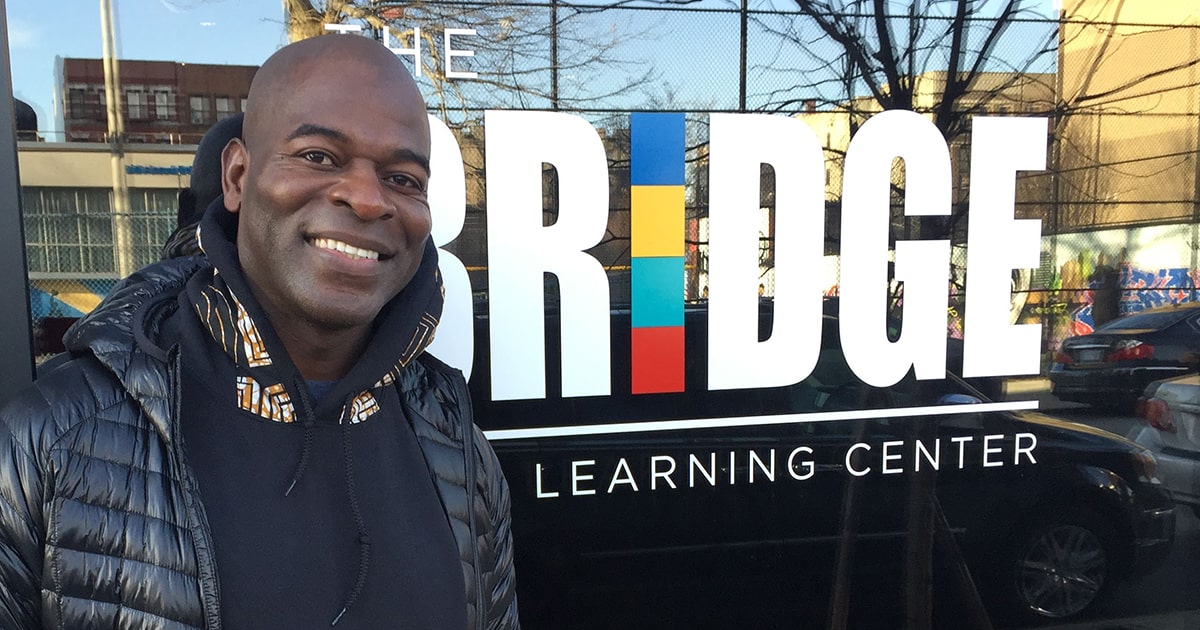

Hisham Tawfiq, a Harlem native who plays Dembe Zuma on NBC’s “The Blacklist,” is a client of The Bridge Golf Learning Center with a unique story to tell. Born into a tight-knit African American Muslim community in Harlem, he went on to serve in the Marine Corps, as a corrections officer at Sing Sing, and as a member of the New York City Fire Department before launching a successful acting career. He recently sat down for an interview with Charlie Hanger, digital content manager for the Foundation and Learning Center.

CH: Tell us a little about your childhood.

HT: My father founded the Mosque of Islamic Brotherhood in Harlem. He was a student of Malcolm X, and after Malcolm went to Egypt and discovered Sunni Islam, my dad also went to Egypt and studied Sunni Islam. He founded his mosque after Malcolm was assassinated, and all of those followers came over to the mosque my father founded.

He started by giving sermons in people’s apartments, and then acquired properties in Harlem and just slowly built this thriving African American Muslim community. So I grew up in that, and I still attend that mosque. I was home-schooled, we had the restaurants, the tea rooms, we had movie nights, we had our own Boy Scout troop, karate school. We had three buildings, and everything was encapsulated in those three buildings in the middle of Harlem.

CH: How did your father come to be a follower of Malcolm X?

HT: He was from Newberry, South Carolina, but because he died when I was 18, and was sick for three years before that, we never really had those discussions. I assume he came to Harlem in the 1960s, became interested in the movement, etc. I’ve learned a lot more about him since he passed, but not those details. And my mother passed away when I was 4, so I couldn’t turn to her for that information either.

CH: Was your Muslim community sheltered from what was happening in the 1970s and ’80s in Harlem?

HT: My neighborhood was heavily drug-infested. We were in this safe haven on 113th Street, but when we stepped off our corner, that was our introduction to everything else. We were bullied, people snatched our keffiyehs, snatched the girls’ headdresses, we had to fight. We didn’t wear jeans, and all of our clothing was homemade, so we were definitely different. But we were so empowered and so trained to have pride that when we did step out we knew what we were defending, as opposed to feeling ashamed or embarrassed.

It wasn’t until I left the 7th grade that I really had to deal with the public school system, which was really different from what I had known when we were home-schooled. And that’s when finding my own identity, navigating between my community and the forces outside, really came into play. We were well prepared for it, but we were teenagers, so there was a sense of peer pressure.

I was the oldest in the community, so I was the first to do everything. When I went to public school, I remember my father did this heavy research and found a school called the Computer School at 96th Street and West End Avenue, but I only went there for about three months before my father had the idea to take the whole family to Saudi Arabia.

We lived in Mecca for a year, and my stepmother taught English at a women’s university. When I came back, I had been on a plane, I had been to another part of the world, but nothing had changed in Harlem. Then I went back to public school, and from there to a high school on the East Side, and that’s when my father passed away.

CH: Your background was not exactly typical for a Marine. How did you end up in the Corps, and what was it like when you got there?

HT: When I was in high school, I knew I was going to the NFL, but then I got injured, my father got sick and passed away, and I had no guidance. I was a dancer with the Repertory Dance Company of East Harlem and had a chance to go to France after I graduated, so I went and didn’t enroll in college. When I came home I got a job at the Apollo, but one morning I just woke up and thought, something doesn’t feel right. I’m going to join the Marines.

When I got to Parris Island, my upbringing was both an issue and an advantage. When you go into any branch of service, they strip you down and rebuild you. I went in there and was like, “You’re not doing anything to me because I already know all of it.” I was in the Boy Scouts, I took karate, I was a swimmer, and I was from New York. I just kept butting heads, but at the same time, they made me the squad leader because I already had the discipline. And racism was mixed in with my experience in the Marines, which left a bad taste.

For one thing, my name was Hisham Tawfiq, so people were always like, “Who the hell are you?” And because of my free thinking and the training I’d already had, I was independent, which didn’t always go over well down South. A lot of my black peers who were from the South used to tell me to chill. And being a proud Muslim, I never shied away from saying, “I’m a Muslim and a Marine.” All of these dynamics combined to make my time in the Marines very interesting, to say the least.

CH: How do you feel about the Marines now?

HT: I still love it. It’s a part of me. Anybody who’s a Marine, it’s something you love, but I did have a distaste for the racism and some of the other power dynamics that came with it.

CH: When you came back to Harlem, you applied for several government jobs and ended up with a job as a corrections officer at Sing Sing. What was that experience like?

HT: A lot of the people who were locked up were from my block. Harlem back in the 1980s was a huge gun area, and we had a huge drug problem. So when I went to Sing Sing, I saw a lot of people I knew from my neighborhood. I mean, I was part of this Muslim community in Harlem, and they were over there, so I knew who they were, but it’s not like these were my friends. They recognized me and tried to take advantage of that. There was also a Muslim population in Sing Sing, and a lot of them knew who my dad was, so they kind of played on that angle also.

CH: And then the Fire Department called. How did the firehouse compare to Sing Sing?

HT: My first day at the firehouse, a senior man met me at the door, and he said, “Are you with the Nation? Do you think all white people are the devil?” I had to give him a course. “I’m a Sunni Muslim, and that’s different from the Nation of Islam, and I don’t believe all white people are devils. I’ve lived in Mecca, and I’ve seen white, black, Chinese — all types of Muslims. Islam is about loving all people, races, Jews and Christians.”

So I gave him this 15-minute course, and he said OK, and we wound up becoming very good friends. But when I started I was the only African American in my firehouse, and for a lot of other people, it was almost like they didn’t want to let go of what they had been told about Muslims or African Americans.

What was really hard was after 9/11. I’d been in the firehouse five or six years, I’d proven myself — didn’t smoke, didn’t drink, worked for people on Christmas because I didn’t celebrate it. But after 9/11, people turned their back on me because I was Muslim, and I was blown away. I responded that day and was at Ground Zero for weeks after. I could’ve died that day.

CH: You spent 20 years as a fireman. What are your most memorable moments?

HT: My best fireman stories are not what a lot of people would think. I grew up on 113th Street. The Harlem Day Parade starts on my block, so I always remember the floats, the people, the food, everything started on my block, and there was always a fire truck. And since I drove a fire truck for about 10 years of my career, eventually I was driving it in the parade, and everybody on my block knew who I was and where I came from, so I felt kind of like the ambassador of Harlem on those parade days.

I was also very active in the recruitment department. I joined the fire department because of the Vulcan Society, an organization of African American firefighters, which goes to the high schools to recruit people of color. They went to my brother’s school, Julia Richman High School, and he came home with a pamphlet right about the time I came home from the Marines. I was taking all these exams, and I saw that pamphlet, and that’s the only reason I applied. So when I became a firefighter, I wanted to do the same thing. I never stopped beating the drum: “Take this job. I did it and you can do it too.”

I’m also very proud of being a drill instructor for the academy. This is normally not the job people want because as a firefighter you have a lot of freedom — when you’re in the firehouse, you can relax, watch TV, work out. As a drill instructor I was getting up at 4 in the morning because I had to be there at 6, and I wasn’t getting home until 7 or 8, and I had to do that Monday through Friday. But I knew what it was like to not see another face in the academy that I could relate to, and that was the reason I went there. The Vulcan Society had campaigned to get someone of color in there as an instructor to be a beacon of hope and familiarity. In my time there, I saw many people who were ready to quit, and I helped them get through the academy, people who I see today and are doing well.

CH: How did you get into acting?

HT: I continued with my dancing up through my time as a corrections officer. I used my vacation time and went on tour with Gloria Gaynor to Brazil and Germany and London, I traveled all over with her. And then I started dancing with a company called Forces of Nature out of St John’s Cathedral, and I danced with them until 1998 or 1999, and that’s kind of when I transferred from dancing into the theater and TV and film.

In the beginning, it was just, “I’m going to try this.” Slowly I realized I needed training. I started taking classes anytime I could. I started off at a place called the Negro Ensemble Company, and then I worked with Neema Barnette, who had this thing called Live Theater Gang, and then I went to Susan Batson, Nicole Kidman’s coach, who has an acting school called Black Nexxus. And then the T. Schreiber Studio, and then Mary T. Boyer, who put the icing on the cake as far as really helping me get to that next level.

CH: How did “The Blacklist” happen?

HT: I had slowly worked my way up to where I had an agent and a manager, so I would go out on these auditions, book jobs, do little stuff, and one day I got an audition for a Saturday in July. Usually you don’t get auditions on the weekends, and I was going to blow it off because there were no lines, it was improv. Then at the last minute I decided to go. I went to that audition, they asked me to come back, and I booked the first episode after the pilot, and then the second episode, and that turned into a year and then two years. At the same time, I was entering my 20th year in the fire department. It was a really hard decision to retire because I loved it, but the show was something I had prayed for, so I had to step into the blessings that God gave me, and I retired.

CH: What advice would you have for young men of color in the city who are trying to get ahead?

HT: If you had asked me that five years ago, I think my answer would’ve been different, because now my son is facing these decisions. I wanted him to go the college route, he was a football player, had done extremely well, but the first semester didn’t work out, and he came home. But then I stepped back and said, “If I didn’t go that route, and it worked out, then he can too.” But I would still say that it’s extremely important for anyone who wants to progress and explore their potential to get the highest form of education you can. My advice to a lot of young people of color is that education is really your ticket out.

And another thing I’ve learned is just to make sure you get out and see the world. Going to Saudi Arabia was really an eye-opening experience for me. Another huge thing my father did was sending me away every summer to a Jewish Boy Scout camp, 10 Mile River in Monticello. That’s where I got my swimming, rowing, canoeing, CPR, rappelling, and many other skills. From the last day of school to the first day of school, I was not allowed to stay in the city. I did that for three years, when I was 15, 16 and 17, and that introduced me to so much that when I came back to Harlem, I knew there was more out there. I always tell kids, look beyond this block, this corner. Expose yourself to more and you’ll be surprised how that will lead to relationships and resources and opportunities.

Hisham Tawfiq has been working on his game with Teaching Professional Randy Taylor at The Bridge Golf Learning Center.

CH: When did you pick up golf?

HT: Growing up in Harlem, nobody played golf. I remember my father was always for me learning sports that everybody else wasn’t playing. So he wouldn’t buy me a basketball; he bought me a soccer ball. We would have to sneak and play basketball with the soccer ball. And then he made us swim, but I was never introduced to golf.

In the firehouse, because I experienced so much racism, a lot of the things that other people were doing, I didn’t want to do, because if I did them, I had to do them with you and deal with the racism. So when it came to golf, to fishing trips — all of that stuff I shied away from. It wasn’t until my friend got married more than 10 years ago in the Dominican Republic that I tried golf. He was a fellow black firefighter and he was going to play, and he asked me to come with him. I went and played and thought, “Oh, well, this is challenging.” After that I was just playing here and there – Dunwoodie, Westchester spots, and when I went down to Savannah to see my mother’s family.

But the bug really kicked in last summer when I went to the Original Tee Classic, which a friend invited me to. I went there and saw Anthony Anderson and John Starks and guys like that, and they were serious golfers. I wanted to be like that, to be able to compete, to be able to keep up, and that tournament was also when another friend told me about The Bridge Golf Foundation and the Learning Center.

CH: Now you’re taking lessons with Randy Taylor and using the TrackMan simulators at the Learning Center. What kind of impact has that had on your game?

HT: I started training with Randy toward the end of last summer. I try to see him once a week, and I do the simulator once a week. Before I started seeing Randy, I was just whacking the ball, but the lessons have changed everything. They’ve changed my appreciation for the game, my understanding of the game, and my mindset.

A lot of people said to me, why are you taking lessons? It only makes it worse. I had learned how to play wrong, only using my arms, and once I started learning how to play right, it was very frustrating because I played better the other way. But I’m seeing the slow progression, and now that I’ve learned to play the right way, I’m not beating up my body so much. I’m not hitting it as far as I used to, but I know I’m going to get better. So now when people say that to me, I say, “You do it your way. I want to learn the right way.”

I used to make decisions with my ego, trying to do something I knew I probably couldn’t do but wanted to try anyway. But when you really learn how to play, you have to put your ego in check and do the things that are within your ability to do. Another focus for me has been the putting game and the chipping game. Now I practice my short game all the time. It probably drives my wife crazy, but I have a wedge in the house, and I’m chipping and trying to get stuff in the garbage can. And the TV stays on the Golf Channel, which I used to despise when I was in the firehouse.