By Matt Matzelle, STEM teaching assistant

Why are some greens “fast” and some “slow”? Golfers understand most of the factors that affect the speed of a ball’s roll — the length of the grass, the slope of the green, the firmness of the ground.

Why are some greens “fast” and some “slow”? Golfers understand most of the factors that affect the speed of a ball’s roll — the length of the grass, the slope of the green, the firmness of the ground.

But most golfers never think about friction, which our young men have been studying in their STEM classes. Friction is the force that resists the motion of two objects in contact. Because of friction, a car’s brakes stop its wheels, heavy objects are hard to push, and rounded objects roll on slopes instead of sliding.

In golf, friction comes into play most in the short game. The amount of friction between the grass and the ball is a major factor in determining the ball’s speed. Longer grass creates more friction than shorter grass, which means shaggy greens are slower than tightly mowed greens.

Friction can be understood by considering the point of contact between two surfaces. Surfaces that may appear smooth to us normally have bumps and jagged edges when viewed microscopically. It is the clashing and grating of these two imperfect surfaces that is the major cause of friction.

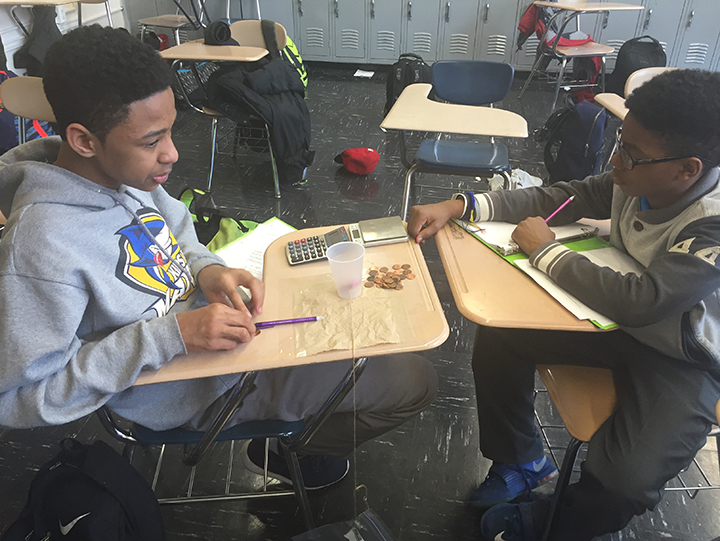

In class, our young men were tasked with developing experiments to find out which variables friction depends on. They were given a list of possibilities, including type of surface, mass, surface area, and whether the objects in contact were moving. First, they covered desks with wax paper, tin foil, and sandpaper. In one experiment, they tied a paper plate to a plastic bag. After weighting the plate with coins, they hung the bag over the edge of the desk and gradually filled the bag with coins until the plate started to slide. As expected, the smoother the surface (i.e., wax paper), the sooner the plate started sliding. The rougher the surface (sandpaper), the longer it took for the plate to slide. In another experiment, they replaced the plate with a plastic cup holding an eraser.

We also demonstrated the power of friction by shuffling the pages of two books together, much like shuffling a deck of cards. When just two pages were involved, it was easy to pull the books apart. When hundreds of pages were shuffled together, the combined friction of all the pages was so strong that no two students could separate the books. We didn’t try it, but I doubt all of our young men together could have pulled them apart.

We’ve had a great week of study and experimentation, and the students have developed a strong qualitative understanding of friction. Maybe someday it might even help them make a few putts.